A Design Research Framework

Get a glorious 20” x 30” print on high-quality heavy paper! Your office needs it. Only $20.

Recent discussions have been swirling around the phrase “democratization of research” concerning who should participate in what kind of research in design (product/service/technology/non-profit etc.) organizations.

There has been a lot of yelling about gatekeeping and handwringing about the potential for low-quality research. The discussion gets shouty when you don’t stop to define your terms and clarify what type of research, to what standard, and for what purpose. Without that, everything devolves into a territory battle.

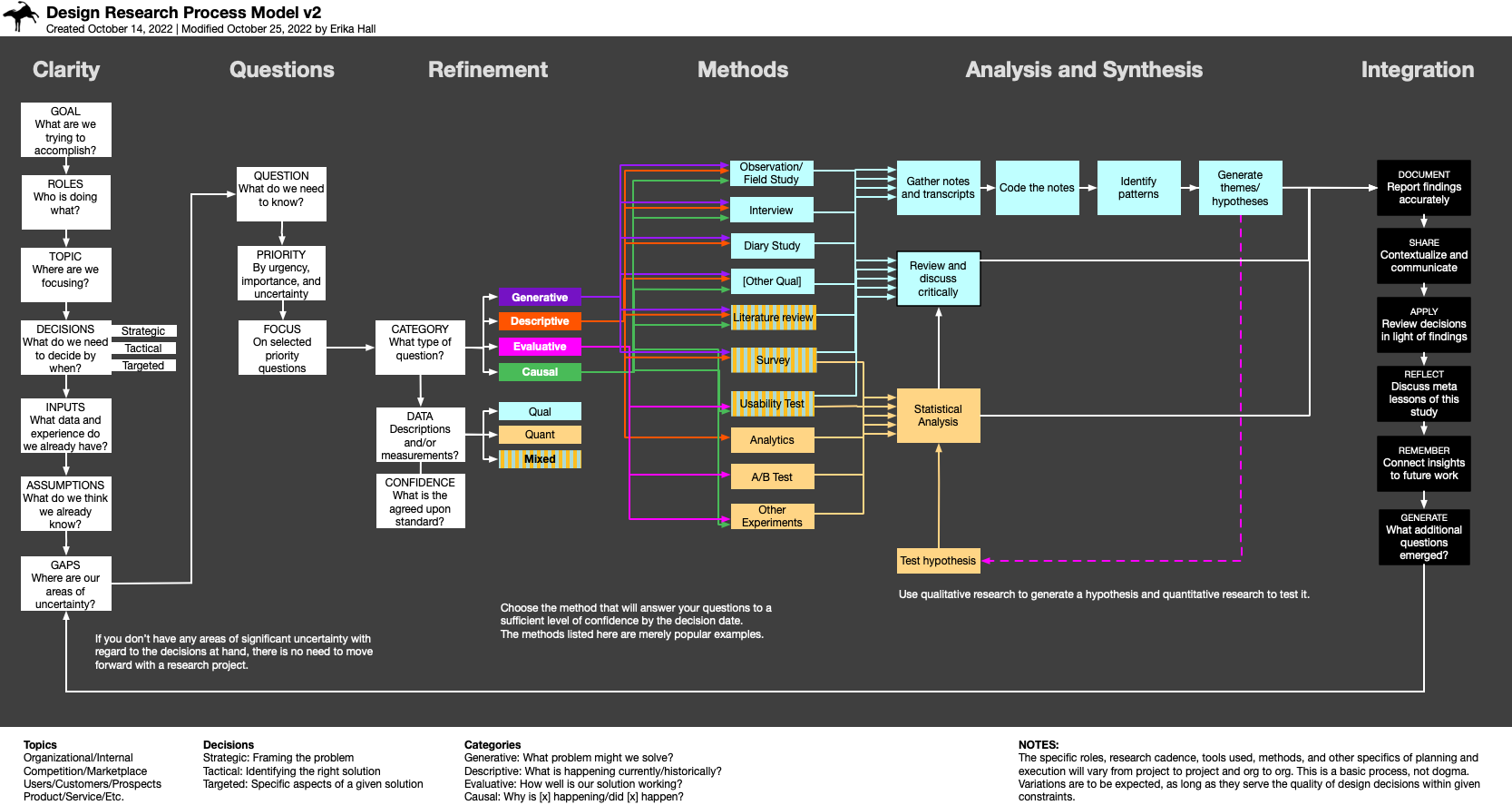

Much of our work involves helping organizations create or develop their design/research practices, so I thought I’d try to help out. I created a cohesive visual representation of the general approach I recommend to clients and follow myself. You can see it above and download the PDF for better resolution.

It looks like a lot when it is broken out into discrete steps, but if your team is already working well together these can often be very short conversations—or even a chat in Slack—and a really small amount of additional documentation at the end. Skipping steps to rush ahead towards false economies or avoid hard conversations is how the wrong methods are applied and value gets lost. That’s the quality issue: everything surrounding the specific methods. Why do research at all if you aren’t going to do it right? Why practice design if you aren’t going to be informed and conscientious about it?

You can just grab the diagram and enjoy, or read further for additional guidance.

(And if your or your team needs help with this stuff, we have a workshop! Or we can work on your deep tissue organizational issues. Just ask.)

Design research?

When I say design research I mean asking and answering questions in a systematic way in order to make more intentional and informed decisions about planning and creating new things and ways of doing things.

Even when I’m talking about research that informs the design of interactive digital systems, I don’t say “UX research” or “user research.” Quite often, the decisions at hand have much wider implications and the information required crosses a variety of topics, including the organization and the design process itself.

Focusing on “the user” exclusively is an easy way to forget about the wider context around that user. And that’s how you get ants, and a lot of otherwise well-meaning designers participating in unsustainable and unethical businesses. Word choice matters. Design is the application of intention, and you are only as intentional as you are informed.

The word “research” contributes a lot of confusion because there are different types of research and different professional standards. Different standards turn into dueling standards in many organizations, which themselves have been poorly designed. There’s that lack of clarity and intention again. Misapplying an academic standard to professional research activities blocks learning. Using research tools and practices without sufficient training and critical thinking can be downright dangerous.

I see design research as a design activity, more than a research activity. What matters most is learning what you need to know in order to make the best possible design decisions within existing constraints. It doesn’t necessarily matter if you uncover anything new, or whether you document what you learn in a specific format. It does matter that you are intentional, conscientious, and ethical at every step.

Roles

Who does what in the design research process varies among organizations, depending on industry, size, structure, capabilities, etc. It may make sense for different disciplines to handle different topics or categories of inquiry. Some organizations will outsource various aspects of the process, or specific types of research question. In all cases, it’s critical to define roles and communication protocols to increase collaboration and information flow and prevent silos and political territories from forming. Aim to cultivate generous expertise, instead of gatekeeping for clout.

How to Use This Diagram

The most important use of this diagram is as a touchstone and a checklist in conversation with anyone who participates in design decisions throughout your organization. Having a basic process to refer to enables more intentional decisions about practice and process, even when under pressure to deliver.

My intention is for this to be sufficiently generic to harmonize with any operating model. Your practice might look slightly different, but always ask yourself: are we doing what is most convenient, or what is most effective? The thing about critical thinking is that it doesn’t necessarily take any more time, especially considering how often fuzzy thinking creates more work down the line, but it feels arduous. Everyone’s lazy brain wants to put everything into procedural memory—autopilot. You can spent 5 minutes on each step, but don’t skip the discussion.

The Phases

Are they phases? Sure. That’s a fun design word for the sequential subsections of the process. The sequence is critical.

Clarity

This is the conversation you need to have before starting on any research project, no matter how small. This is the conversation you should be having on the regular, regardless. Both collaboration and effective design research require clear goals and roles. You need to understand what level of decision you’re talking about to know how much time and effort you should invest in answering your questions. The time-and-budget-based objections to research are fake. Just back your whole plan out from when you need to make a decision. You can always learn something useful if you’re clear on what you need to know and by when. If you need an entirely new product strategy by tomorrow, ask how you ended up in that spot. It’s probably because someone was avoiding these conversations.

It is highly productive to spend an hour with your team separating your knowns from your unknowns, and establishing what your knowledge is based on. Maybe that is all you need to do.

Questions

Once you have identified the information gaps that either block your work or add risk, move ahead to forming research questions. Just because you identify a question doesn’t mean you need to answer it immediately. Brainstorming questions is another really productive activity not enough teams do. It is far more useful and collaborative than brainstorming ideas. Keep a running list. This will prime everyone on your team to keep their antennae up for ambient insights. Learning can come from anywhere if you’re screening for it and thinking critically.

Select your highest priority question/s to carry forward and turn into actual research projects.

Refinement

This is when you get really clear on your question, before choosing a method. How you phrase your research question (again, not an interview question) determines what is possible for you to learn. Do you need ideas, or descriptions of what happens in the real world? Are you at the point of evaluating a solution? (Don’t say “validate” or I’ll haunt you.) Are you trying to establish a cause and effect relationship? Do you already have a hypothesis to use as the basis for an experiment? (A hypothesis is an explanation based on evidence. If you merely have a wish, you do not have a hypothesis.)

Be very clear on whether you need qualitative or quantitative data, or maybe you need to do a mixed methods study to establish and validate a hypothesis, for example.

And talk about how much of what kind of data you need to be confident in your decision. This is the time to discuss the concept of qualitative saturation with your business stakeholders, not when you’ve already done the study and they’re saying “pssh, 8 users”. If you need quantitative data, make sure you’re working in the realm of the actually measurable and potentially statistically valid and also relevant to your decision.

Methods

Now you get to choose a method. Research methods and activities are simply ways to answer your question. There’s no one right method. Pick the one that will give you the kind of data you need to inform your choices. And consider the colorful lines serving suggestions. Maybe you get some generative-style ideas from running a test on your competitor’s product or service, or on your own. The key is—say it with me—being intentional. Using the tool or the method is not learning. Learning is learning.

When you consider timing, scope, and scale, make sure to account for planning, conducting, and all of the analysis, synthesis, and follow-up.

Maybe you only have time to read articles and reports that are publicly available. There is a LOT of information out there a clear research question can unlock.

Analysis and Synthesis

The type of analysis you do depends on your question and method, so in some sense, this is the easy part. The learning to arguing ratio should be much higher here if you’ve followed all the proceeding steps. This is also the potentially time-consuming part. Sometimes you will need to do a few rounds of analysis.

It’s too big of a topic here to go into detail here, so I’ll just say, you should have planned how to approach analysis and synthesis when you chose your method, including roles of everyone involved.

Integration

So many organizations invest so much in doing research activities, and then POOF, it’s like the work never happened. Look ahead to integrating insights at the very beginning. How and when you go about documenting and communicating will depend upon how the organization as a whole works. One more process to design!

A “research repository” is not a substitute for the necessary interaction and communication among humans.

And finally, gather up all of the the other questions that arose and add them to your ever increasing collection of known unknowns. Questions are awesome.