Brainstorm Questions Not Ideas

We vastly overvalue the idea of “ideas” in design. Meaningful additions to the world rest on novel connections among pre-existing concepts, objects and situations, not self-indulgent originality for its own sake. What we glorify as flashes of brilliance are usually astute observations about the world, improved by critical thinking and critique. And observations often begin from a question.

However, because many of us have been rewarded and praised for having right answers and clever ideas, in school as well as in professional life, the questioning and critiquing part of design can get very uncomfortable. So much easier to sink into the fluffy pillow of groupthink.

Brainstorming ideas and solutions together is an extremely popular activity because it feels collaborative and creativity-enhancing even when it’s really not. Research has shown group brainstorming to be a waste of time. In addition, brainstorming ideas is often anti-collaborative. Everyone secretly, or not so secretly, wants their contribution to "win". And once you frame an exercise as “there are no bad ideas”, well, that’s how you get ants, and really bad ideas that make it out into the world because no one wants to be the bummer or stick their neck out or kill that one lovely darling that already made it into a prototype so we might as well ship it. The Emperor's New Clothes plays out on the daily.

A quick and effective fix is to stop brainstorming ideas with your team, and start brainstorming questions instead. Getting together and listing every question you can think of about a problem, a process, or a situation is uncomfortable at first, and then in very short order enhances collaboration, decreases risk and puts you on the path to being a learning organization.

Whether you’re confronting a lack of clarity or a wellspring of curiosity, getting it out in the open contributes to shared understanding and shared goals, and is far more efficient than pretending mutual understanding. You can fire up the Mystery Machine and investigate together.

Known unknowns are interesting and manageable. Unknown unknowns will jump out and bite you.

How to run the conversation

Excuses to avoid asking questions abound just because it can feel so risky and uncomfortable and daunting at first. So, frame the first try as just that. Take an hour, or even 30 minutes, just to get a bunch out and roughly sorted.

Participants may feel like they need permission to ask anything but the safest, smallest questions, so give it to them. Depending on the group, you may need to prep a couple of more senior people in advance and ask them to model admitting what they don’t know.

I bet you’ll soon start hearing a chorus of “Hey, I was wondering that myself.”

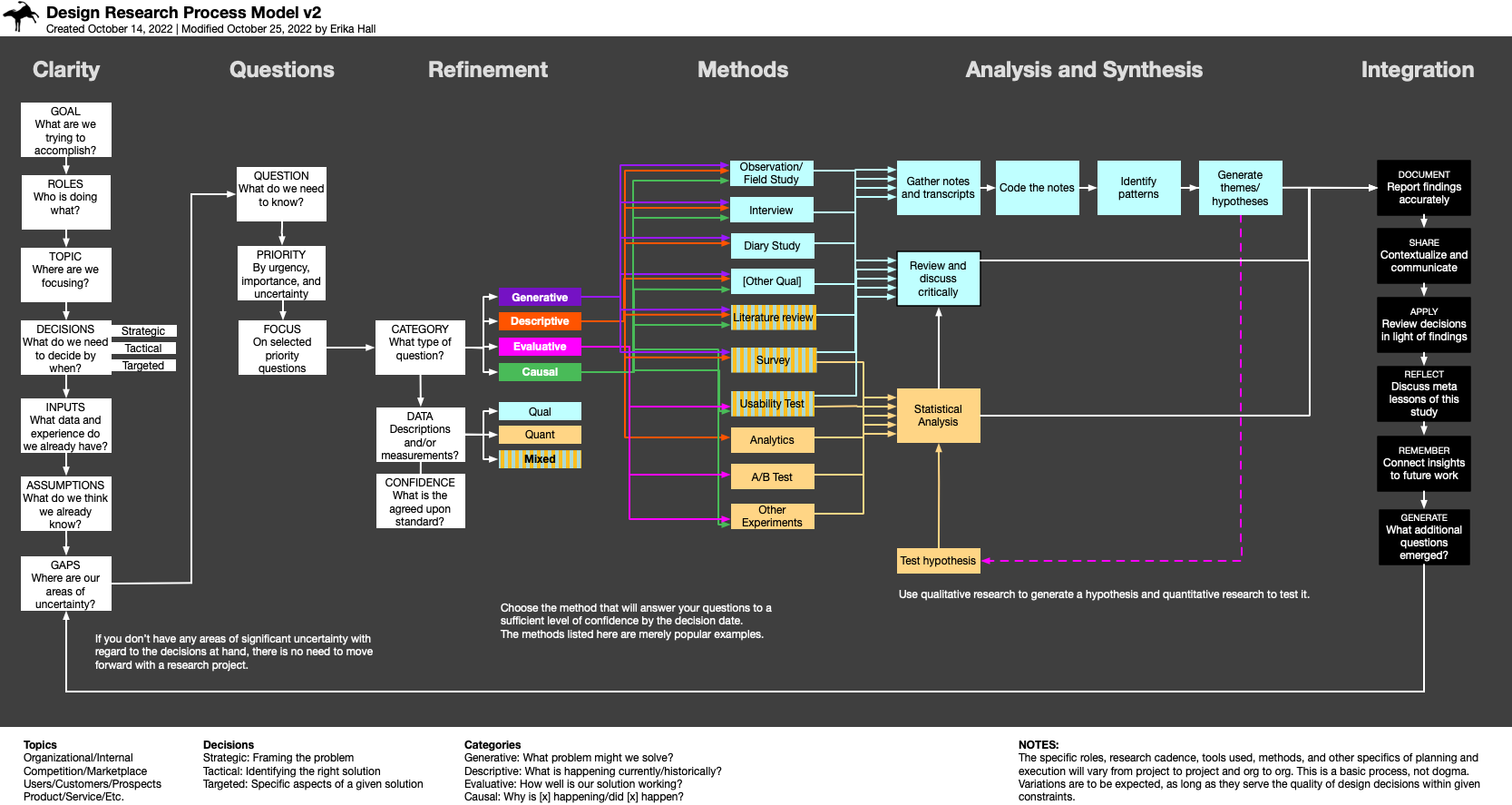

Follow these simple steps in order, and explicitly time-boxed from the top:

Identify the most important goal/decision at hand (this could turn into a discussion, or start with prepared material to work from)

Take suggestions for any and all, large or small, questions it might be helpful to answer

Once you have all your question, plot them according to how little you know and how critical it is to find out

There should be some room for discussion and refinement to figure out whether you have one question or several. That is a very productive use of time as long as it doesn’t get into unhelpful semantics. If you have time, you can make categories or work up an affinity diagram.

It should go without saying that before you plan any design research, and especially before you decide on any particular research activity or method, you should go through this exercise with your team and as many decision-makers as possible. Helping to articulate the question makes everyone much more invested in the answers.

Maintain a canonical list of questions. Review it regularly. This alone will make your team smarter and encourage curiosity and observation.

Enumerating and categorizing your questions doesn’t commit you to answering them in any specific order, or at all, but it’s the only way to determine which are worth putting resources into investigating. And once you get in the habit, it’s a short conversation. (If it isn’t, well, that’s an important thing to know.)

Priming your team to be thinking about the same important questions in the same words will lead to better collaboration and more insights in a shorter amount of time. Also, it's a good way to increase comfort with admitting ignorance.

"I don't know…" should be easy to say long before you start down the path of "How might we…".